Trending

Texas booms in the Cloud and on the ground

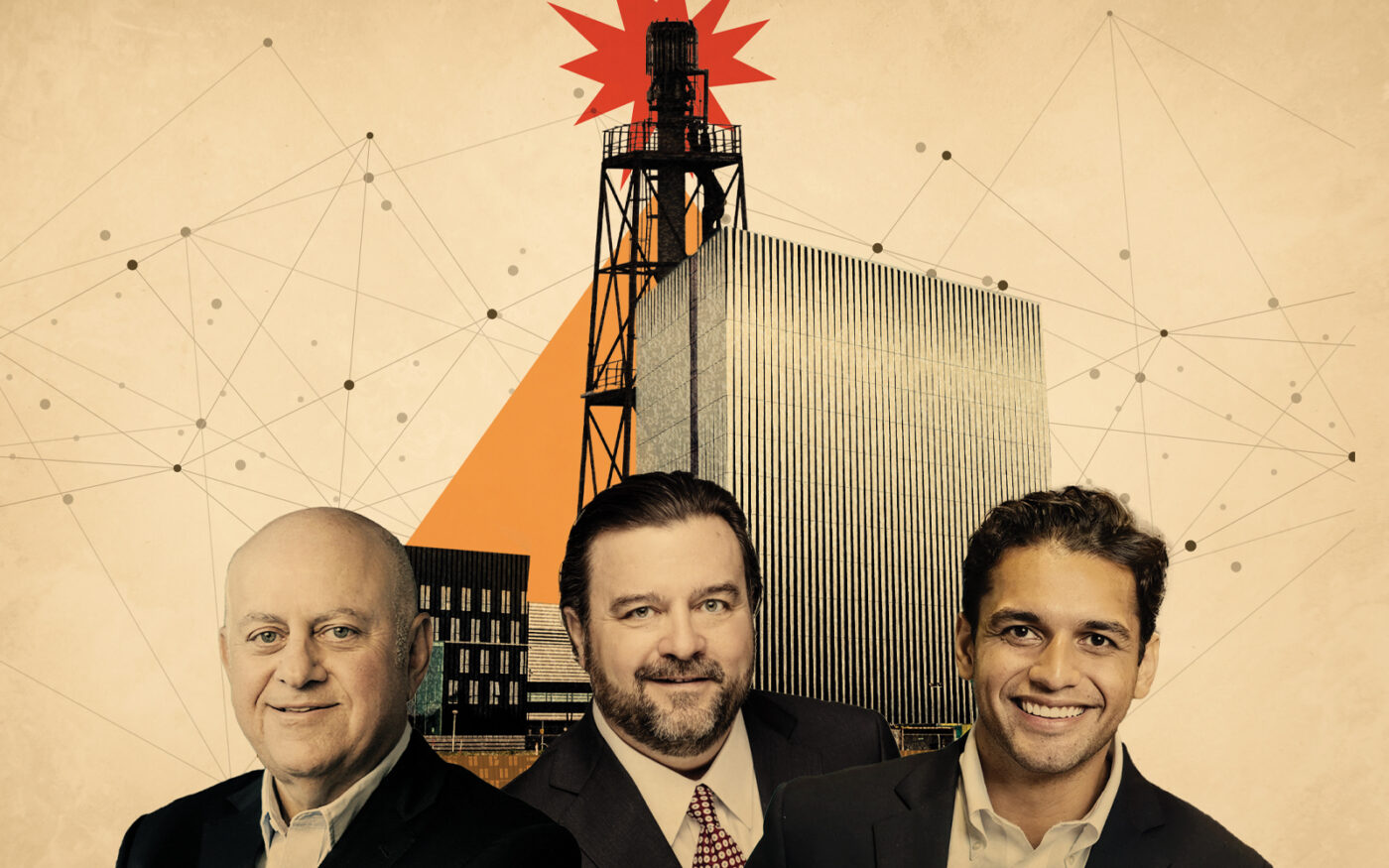

As the AI boom fuels a rush for data center space, Texas farms become development sites

There’s nothing high-tech about Highway 79 in Hutto, Texas — at least not yet. But soon, a lonely stretch of pavement cutting through farmland will be more than just another country road. It will lead to the doorstep of the AI revolution.

Hutto, a fast-growing city about 20 miles north of Austin, shot to prominence this past spring, when Prologis and Skybox announced they would build a $10 billion data center on Highway 79.

The city was known mainly for its obsession with hippos; it’s a place where statues of the river horses crop up on lawns and park benches like an invasive species of garden gnome. But now tech giants, real estate developers and private equity-backed builders are buying up hundreds of acres of land in Hutto to build state-of-the-art data centers.

Even before ChatGPT launched a boom in artificial intelligence investment, the pandemic had made it hard to find space in data centers. Now it’s nearly impossible. AI models require enormous amounts of power and computing capacity worsening what was already perhaps the most acute supply-and-demand imbalance in real estate. That means big money is pouring into larger projects in unlikely places across Texas, like Hutto.

No vacancy

In more than 20 years working with data centers, JLL’s Curt Halcomb has never seen this much land under contract for new developments. As recently as 2019, developers were building on 30- or 40-acre plots — now his clients want 300 or 400 acres.

Why do we need data centers the size of Disneyland? Part of it is the way lives shifted online during the pandemic — with all those eye-glazing hours of Zoom meetings and social media scrolling, humans are generating an unprecedented volume of data.

But AI models will soon produce even more data, exacerbating the need for somewhere to store it all. A single language model can require 1E12, or one million million, data points — and techies are building models that generate more data just to train even more models. Gartner, a research and consulting firm, estimates that by next year, machine-generated data will constitute 60 percent of the data used in AI training.

While all that data does require more physical space, the bigger constraint in adding all those computers is power. AI models run tons of calculations, drawing unprecedented amounts of electricity for software. Those racks of computers draw five to six times more power than similarly sized racks running traditional applications. Experts tend to describe data centers in terms of the megawatts they draw, not the square feet they cover, and AI has only made power even more important.

“I don’t really look for land anymore. I’m looking for power capacity,” Holcomb said.

Where older data centers typically run on less than 30 megawatts, the new megaprojects require hundreds. For reference, Lubbock, Texas, a city of about 261,000 people, draws about 600 megawatts, according to Holcomb.

Even as developers rush to build, they are penned in by utilities.

Most space in data centers delivering late this year or next year is already pre-leased. And as the uses of AI and new firms trying to harness the technology grow by the day, so does demand for space. Tenants leased space for some 2.1 gigawatts in the second quarter of this year — roughly equivalent to the power generated by two standard nuclear generators — and in Dallas alone, demand from AI is expected to require another 360 megawatts, according to a report from JLL.

“If you’re a Fortune 1000 company, a cloud provider or an AI company and you want data center capacity, you better be looking now, because depending on the market, you may not be able to get it until 2025,” said Holcomb.

Still, development has ramped up dramatically. In the first half of 2019, there were only around 100 megawatts of new space in the pipeline — in that span this year, there were more than 3,000. Leasing has kept pace — in the first half of 2019, the market absorbed just under 200 megawatts of space at data centers. In the same span this year, it absorbed a little over 1,000 megawatts.

The space is dominated by 10 to 15 big players, including Microsoft, Meta, Amazon and Google. The so-called “hyperscalers” and “colocators” provide web and hosting services for countless smaller businesses, and make a mint in the process.

But tech giants are becoming data center developers themselves.

Meta owns 21 data centers around the world, according to its most recent annual report. It is building an $800 million facility on just under 400 acres in Temple, Texas, and has invested $1.5 billion in its 2.5-million-square-foot center in Fort Worth.

“If you’re a Fortune 1000 company, a cloud provider or an AI company and you want data center capacity, you better be looking now.”

Alphabet, Google’s parent company, opened an 800,000-square-foot data center in Midlothian, southwest of Dallas, in 2019, and recently announced a new $600 million data center in Red Oak, south of downtown Dallas.

Even as rates slow deal flow in real estate markets in a variety of sectors across the country, data center developers are actively searching for new sites.

“If they have land that they can build on, they’re probably already building or planning to build,” Holcomb said. “However, most of them are out in the market looking for that next campus.”

Private equity giants are getting in on the action, too.

Blackstone took QTS, a data center-specific REIT, private for $10 billion in 2021, calling the explosion of data one of the firm’s “highest conviction themes.” The next year, KKR and Global Infrastructure Partners bought Dallas-based CyrusOne for $15 billion. In 2022, private equity accounted for 91 percent of the $48 billion spent on data center mergers and acquisitions, according to JLL.

Even with all this investment, supply is woefully short.

In Dallas-Fort Worth, the longtime leader in Texas data centers, just 2 percent of the metroplex’s 4.8 million square feet of data centers is vacant. Some 4.2 million square feet of space is planned, and it will draw on 1.5 gigawatts of power — twice the amount used by the city’s existing data centers — but much of that is already pre-leased.

“In every market, there’s a grab for available capacity,” said Anubhav Raj, CFO of Aligned Data Centers. Aligned focuses on building 50- to 100-megawatt campuses like its Dallas-Fort Worth spread, where one 10-megawatt facility is operational and a second, 36-megawatt center is on the way.

Interest is growing in South Dallas, the majority-Black neighborhood that has long lacked the infrastructure and real estate investment of other parts of the city. Still, the overwhelming demand for space amid the AI boom is pushing developers out to greener pastures, like those in the rolling farmland on the east side of Hutto.

The Megasite

Hutto has always connected to the outside world via the land near Highway 79.

The town’s train tracks, built in the late 19th century, cut the first path through the farmland of Hutto’s east side, connecting its few, scattered residents to the International-Great Northern Railroad network. As Americans began to prefer cars to trains, Highway 79 brought Hutto into the automotive age, running parallel to the train tracks just a few feet to the north.

Now the nervous system that connects the world is largely invisible, as the internet whisks emails and posts between wireless devices in a blink. But the data centers that host it are just as physical as the railroad and highway, making them some of the most critical, in-demand real estate on Earth. In Hutto, on a 1,500-acre “megasite” along the railroad and highway, investors are pouring billions of dollars into building next-generation centers that can handle not just websites but the data- and energy-intensive AI models that are revolutionizing the way we live and work.

Like so many of the boomtowns on Austin’s outskirts, Hutto has the feel of an active construction site. Earthmovers and temporary fencing pepper the landscape. Approaching the main drag from the south, the only structure that evokes a reaction is the gigantic high school football stadium, home of the Hutto Hippos. Empty lots sit next to newly built single-family sprawl. Where sidewalks exist, you could eat off them; lawns are Home Depot-commercial quality.

The population has more than doubled since 2009, from 18,000 to 36,600. In 1990, when the modern data center was coming into existence, just 630 people lived in Hutto.

But the most exciting developments are happening due east of the town center along Highway 79. There lies the Megasite, where Hutto’s economic development corporation owns 450 acres and has options to purchase another 1,000, according to the Austin Business Journal.

There’s not much to see right now other than empty fields and an isolated shack. But hundreds of acres along the highway are owned by some of the biggest players in industrial real estate.

On 160 acres of former farmland where the highway meets County Road 132, Prologis and Skybox are building a $10 billion data center campus with as many as six buildings totaling 4 million square feet. The site includes two private substations capable of converting the high-voltage power carried by nearby electric lines into 600 megawatts of electricity.

In nearby Pflugerville, the developers are wrapping up Skybox Austin I, a $548 million data center with 30-megawatt capacity.

Industrial development of all stripes is coming to Highway 79. Samsung is building a $25 billion chip plant, its biggest ever U.S. investment, where the highway meets County Road 401. On Farm-to-Market Road 3349, Titan Development is building a 188-acre warehouse park it’s calling Hutto Mega TechCenter.

In the Austin-San Antonio market at large, just 5,000 square feet were vacant at the end of the first half of the year, according to JLL. With 4 million total square feet of space, that’s a vacancy rate of less than 1 percent. Nearly 8 million square feet of new space is either under construction or planned, a 200 percent increase that will fundamentally reshape the region’s data center market.

Short circuit

During the crypto craze, developers built cavernous computer facilities across Texas to mine the coin, which has fallen about 50 percent since its peak in October 2021. While some of these buildings, like Riot’s 750-megawatt facility in Rockdale, can also be used as data centers, the bones of disused mining projects are a stark reminder of how quickly tech’s Next Big Thing is reduced to just another thing.

AI has clear real-world use cases, some of which are already more impressive than what the crypto era produced. But with the needs of the technology changing so fast, it is hard to build today what we will want in the future.

“If anyone tells you they know what AI is going to do, from a demand perspective over the next three years, I would call BS,” one data center executive said.

While investment in the sector is still high, generative AI deals fell by 29 percent in the third quarter of this year, Pitchbook reported in October. Enthusiasm for the sector may be waning as the largest tech companies make the biggest leaps forward.

Rex Glendenning, a veteran North Texas land broker, said he hasn’t seen much interest from data center developers, at least in his listings.

“I have seen a few deals that are being promoted in south Dallas around Red Oak, et cetera, but we haven’t felt the surge of interest as of yet,” he said.

As private equity giants up their bets in the Sun Belt, there are concerns. Wolfe Research, a capital markets research firm, recommended that analysts ask executives from data center REITs whether they think Blackstone investments might lead to oversupply.

The most critical challenge is whether the state can generate and transmit enough energy to power data centers. Texas is a worthy contender, producing the most oil, natural gas, wind and solar energy of any state in the nation. Still, the facilities can put a huge strain on local utility capacity and infrastructure, with many developers paying out of pocket to build their own substations.

For all the ways it could go wrong, the data center boom is shaping up to transform Texas’ industrial real estate landscape, and investors see dollar signs everywhere.

“I would love to buy every acre of land around Dallas, Fort Worth, Austin or San Antonio that is exactly contiguous with a substation or switch station,” Holcomb said. “I bet you could probably go out and raise money to do that. I just kind of thought of that.”