Trending

Rechler responds: RXR boss on health of his office portfolio

In a sit-down with TRD, developer discusses office conversions, construction finance and proptech “fantasyland”

RXR’s Scott Rechler (Getty)

Scott Rechler is in damage control mode.

A Financial Times article Thursday headlined “New York property tycoon to give worn-out offices back to the bank” rippled through the real estate industry. If the mighty RXR is facing a reckoning with lenders, readers thought, what hope is there for everyone else?

As The Real Deal and other outlets picked up the news, Rechler sprung into action, working the phones to clarify that the “worn-out offices” were only two properties in a roughly $20 billion portfolio. He fired off a letter to investors Friday morning calling the FT’s headline “sensationalistic” and said RXR had already made back its equity on one of the properties — reportedly 61 Broadway in Lower Manhattan — upon selling a stake in it several years ago to a Chinese state–owned investor.

The message was clear: Nothing to see here. But in a shaky market with spooked lenders, any sign of weakness can compound, so Rechler sat down with TRD to talk about the health of his portfolio, what he thinks needs to happen to trigger office-to-residential conversions and why he still feels there’s heaps of money to be made in New York’s office market.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The FT article about RXR caused quite a stir, so let’s clear it up. What exactly is happening with your office portfolio? Are you surrendering buildings to your lenders?

We want to be honest with ourselves as to which buildings are going to be really competitive in the post-pandemic world. I made the analogy of Kodak — there was a time that film was going out and they were investing in it, but in reality, they should have been investing in digital. That’s what I’ve called it in our company: Project Kodak. Let’s focus on what [buildings] are digital and which properties might be film. The ones that are film, we need to then look at differently.

We’ve narrowed those down to a handful of buildings. Is there an alternative use that’s not office? And right now, we’ve identified two buildings, one in Lower Manhattan and one in Brooklyn, that we’re in the process of pursuing a conversion to mixed-use.

Read more

To make them work, you need to work with the lenders to get their approvals to inject the type of money that’s required. In some cases, you need to go for a zoning change. In the instances where they don’t work, the point we made to the FT was, we’re not going to continue to throw good money after bad.

You’d walk away on those two if it didn’t pencil out. Got it. But what conversations are you having with your lenders portfolio-wide? You are one of the largest office landlords in New York. You’ve worked out that up to 10 percent of your product could be “film.”

The liquidity in the lending market for office buildings has definitely contracted. There’s a clear, existential change happening in how people use office buildings. Many lenders are painting every office building with the same brush. If you’re a lender, you really don’t want to go to the credit committee with an office building. You’d rather go multifamily, because offices are under much more scrutiny. So you’re at a point where lenders are backing their best clients, backing owners willing to invest additional capital into those buildings, and then they’ll extend loans or refinance.

We did that at 5 Times Square, where we invested $300 million. We did that at Starrett Lehigh [601 West 26th Street] where we’re investing hundreds of millions in building out amenities and tenant spaces and have gotten extensions on those loans. And this goes back to my earlier comment: The buildings we’ve deemed digital, we will continue to support.

You’re also seeing opportunities on the lending side. I believe you have $2 billion earmarked for that. Have you started putting that money to work?

Yeah. We invested $250 million at the end of last year in the Solow portfolio [purchased by Josh Gotlib’s Black Spruce Management and Meyer Orbach].

It had good existing debt, agency debt, that was 40 percent or so low leverage, but it required a large equity check. So we came in and provided preferred equity.

What you’re seeing is not only are banks being more constrained, but nonbank lenders, too. Even multifamily properties that were under development or being acquired with underwriting that assumed an interest-rate regime that existed before the big spike, don’t pencil out in the new interest-rate mix. That’s where we can step in and help fill that void. In this situation, you’re able to make debt-like investments, but get equity-like returns.

That being said, given where LIBOR or SOFR [a LIBOR alternative] is right now, if you add any reasonable spread, 300, 400 basis points, your borrowers are paying 10 percent anyway, even for senior loans. So the alternative isn’t cheap.

Do you ever eye taking control of some of these deals you invest in?

We try to be more of a value-add lender. We have the ability to help underwrite construction risk, evaluate capital projects, things that are a little bit more hairy. That enables that borrower to give comfort to the senior lender. The goal is not loan-to-own.

Now we do have a strategy on the acquisition side which we’ve been very active on: Buying buildings that are under construction. Usually from merchant builders that have been delayed or their costs have gone up and their promote would be gone if they had to get through completion, stabilization, and then sell. We’ll step in and pay a price at which they’ll still be able to recognize a promote, and we’ll take the risk of overseeing them completing construction and lease-up.

You’re not quite the sponsor in that case. More like a hand on the shoulder.

We will buy it and we’ll let them recognize their gain and hold back money for completion. We’ll let them complete the project and when they’re out, they’re out — we’ll give them the rest of their money.

First, it was the pandemic — everything got delayed, which wiped out a lot of promotes. And these are merchant builders that plan on selling anyway. With the interest rate rise, and construction costs rising, they didn’t account for having to put interest rate reserves or the cost of interest-rate caps that have gone up almost 10, 20 times what they originally forecasted. It’s thrown their loans out of balance. So we can step in and resolve that, either through refinancing or acquiring midstream of construction.

With all this talk of the office as an existentially damaged asset, how do your international investors — the sovereigns, the pensions — feel about the megaprojects you’re taking on, like 5 Times Square or 175 Park Avenue? I wonder if the tenor of those conversations has become more philosophical.

We tend to be ahead of where the market’s going. When we sold our company in ’07 and came back in August ’09, there was lack of clarity about the future of New York, where the office market was going, where the financial sector was going. We had communicated where we think the opportunity is to our investors, and so we invested $4.5 billion in a two-year period in office buildings and bought buildings like Starrett Lehigh for a billion dollars in the days when [those were record deals].

“My big caution when I speak to policymakers is, ‘Do not try to solve every problem in lieu of this one big problem.’”

Every year, we write a white paper thinking through what’s happening in the world, what’s happening in our markets, what’s happening politically, in the economy. And from that paper, we derive conviction as to what we want to do. Sometimes it could take two or three years before we actually see opportunities that fit the strategy we described. But by the time we see it, they [investors] realize that we’re not just being reactionary. It also ensures that we maintain discipline. In real estate, there’s a lot of exciting deals that come in.

Our mutual friend Dror Poleg highlighted this consumerization of the office trend: What happens when the office goes from somewhere you need to be, to somewhere you have to want to be?

Thinking about the merger of work and home, life and hospitality has been at the center of how we’ve approached the workplace for the last 10 years. The glue that brings that together is a sense of community. Places that people can go eat, health clubs, art and culture. And then even the communities around our building. What are the small businesses? What are the restaurants? How do we create programming? And how do we create the relationships so that the people who work in our buildings also become good users of those businesses?

There have been so many different pleas for return to office, from collaboration to career development to civic and even patriotic duty. If you had to pick one reason to come back, what would it be?

All those things have different stakeholders and rationales. But the real reason is that to have a rich and vibrant career, you need personal engagement, you need community, you need mentorship and friendships. To me, it wasn’t a surprise that the Great Resignation was happening because it was like, “Scott decides he wants to change his job, he changes his Zoom account, his email address.” [Laughs] It wasn’t changing my commute, there was no going to the office and packing up the boxes and saying goodbye and people crying — there’s no connectivity.

But I don’t want to let go of the other points. The civic duty piece is that we as individuals need to recognize that if we’re not coming to our city centers, there are challenges to the small business owners, the restaurants, the service workers. To our city ecosystem, to how our transit systems are going to be funded. We have to be thoughtful about policy to address those problems.

Mayor Adams is proposing rezoning Midtown to allow for more apartments, and Gov. Hochul just floated an office conversion tax break. What else do you think needs to happen to make conversions viable?

We need to provide certainty around the regulatory environment. You can’t have to go through Ulurp and years of uncertainty about whether or not you’re going to be able to convert a building. We need a regulatory framework that creates as-of-right conversion opportunities. Like at the Midtown East rezoning: They laid out the rules of the game, and that’s why you see a One Vanderbilt, that’s why you see a JPMorgan [270 Park Avenue], a 175 Park. It sparked the private sector to bring its innovation and entrepreneurship in to get that done. So that would be a big factor combined with tax incentives.

“Given where LIBOR or SOFR is right now, if you add any reasonable spread, 300, 400 basis points, your borrowers are paying 10 percent anyway, even for senior loans.”

My big caution when I speak to policymakers is, “Do not try to solve every problem in lieu of this one big problem.” We have a housing shortage and we have buildings that are going to be competitively obsolete that are great alternatives to convert to housing. To make that work, they have to likely be market-rate housing. Now, we also have an affordability problem, but that’s a separate problem, let’s solve it separately. Because if you try to solve this problem and say, “Ok, but X percent of it has to be low-income, you have to use union labor,” we’re never going to get it done. Like California.

A new labor bureau report shows that for the first time in four decades, Florida has added more jobs than New York. A lot of the dynamism and talent is moving south. So, yes, New York is still New York, but the momentum has shifted to the Sunshine State.

We’re in Florida, we’re in Arizona, we’re in those markets. The regulatory environment is much easier — it’s night and day. But you come to New York because there’s no place that has as much culture, diversity, or economic opportunity. Think about the scale of places like Miami — It’s small.

And I’ll say this: In 2020-2021, when everyone was running away from New York, we bought $2 billion of multifamily buildings when they were 80 percent occupied, at big discounts. And now they’re 99 percent occupied and rents are above 2019 levels. New York’s No. 1 natural resource is talent. And the talent pool has continued to be here, which gives me great confidence.

Let’s talk tech giants. Google had hypergrowth in the pandemic and ended up adding about 70,000 workers. Now they’re making very significant layoffs, as are other big players, who seem to be coming to a realization that they can do what they do without as big of a workforce. That hurts the office market in the long term.

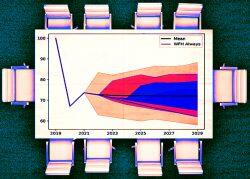

That really was a pandemic demand surge. The tech companies played into that, the retail companies did in terms of inventory, and the investment banks in terms of transactions. And there’s going to be a reversion back to 2019 trend lines. It’s almost like we had a fantasyland of all the surge of demand coming out of Covid. That was nice to have, but it’s not sustainable.

What does that mean for offices? I don’t think we ever underwrote in our business that we were going to have that surge. So if we get back to ’19 and start growing from there, I think that will be fine.

175 Park, where you’re doing hotels and office, hits upon something I think a lot about, the blurring of asset classes. You tried a partnership with Airbnb at 75 Rock as well. The next iteration of building may well be many buildings in one.

I could see the same thing in our multifamily residences, where we’re building workplaces and meeting spaces. Now that doesn’t necessarily have to always be in one building, but you’re clustering around the neighborhoods that those buildings are in.

How do you structure the capital stack for these multi-pronged assets?

You generally have to underwrite each use separately, and then consolidate it for the financing. In some cases, we’ve developed programs where you can actually [create condo interests] and finance each part separately. We’re looking at that in some of our conversion opportunities.

“New York’s number one natural resource is talent. And the talent pool has continued to be here, which gives me great confidence.”

At a lot of our buildings, we have Convene. We have flexible workspaces, meeting rooms, lounge areas. And we try to use their hospitality to service everyone in that building. We’re rolling that out [across the portfolio], so it’s almost like living in a hotel when you’re in an office building.

Convene is an interesting business. Had the pandemic not hit, I think it would have been huge.

I’m an investor and a close friend of Ryan’s [Convene co-founder Ryan Simonetti]. If you had to pinpoint the epicenter of the crisis, it was everything that Convene was converging on. But credit to them for navigating through.

Maybe you didn’t lose any money on it, but I doubt you made money.

But we’re doubling down, as most of the investors have as these other [funding] rounds have come through. You believe in the business, you stick with it. But the world of rocketship growth has changed. You go away from a world of free money where you see these crazy valuations, which then spark crazy acquisitions. Like a lot of the former SoftBank companies were “go big or go home.” When I work with them, I’m like, “No, no. It’s get profitable or go home.”

What you said makes sense, but maybe 1 out of 100 proptech startups followed that model, prioritizing profitability over hypergrowth.

There was a psyche, driven by excess liquidity in the marketplace. Venture capital never had this much money. As venture capital began to be capitalized more like private equity, which can usually write bigger checks, there was a lot of money chasing a relatively small number of opportunities. So it began to fuel valuations, which you then had to grow into. [Laughs]

We’re going into a more normalized higher-inflation, higher interest–rate environment, which is going to create a period of transition. It is probably going to be very good on the other side, because you’re going to have a period of growth around decarbonization, deglobalization and digitalization. But crossing that chasm is not going to be without pain.

(Write to Hiten at hs@therealdeal.com or @hitsamty on Twitter.)